China Population Aging:

As China nears 1.4 billion inhabitants and becomes one of the most powerful economies in the world, the country has had to prepare and adjust to vast changes accordingly. The highly dynamic setting has brought on many unprecedented scenarios, yielding a plethora of new opportunities as well as looming hurdles. Of these ongoing developments, one of the most crucial unfolding issues is the matter of China’s ageing population, and how to handle it.

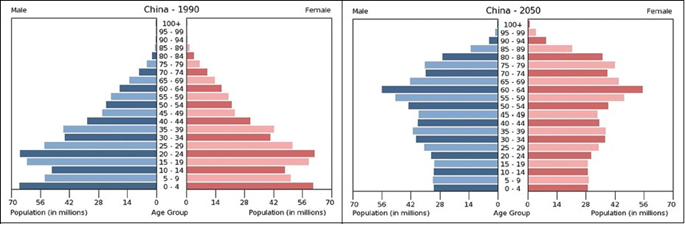

The given of China’s ageing population is no surprising prospect, and has long troubled members of Chinese society ranging from scholars to government officials, economists and age groups of the young and old. A consequence of China’s one child policy, which significantly disproportioned the size of generations, paired with China’s still steadily growing population, China is today heading towards a future where the older generation will significantly outnumber the younger one.

To many, having a massive population of older generations is perceived to be a potential burden and a sign of impending mass dependency and limited efficiency. As average populations usually are distributed more heavily towards middle and younger generations, China’s ageing future is an unprecedented situation that is difficult to forecast:

Will there be a sudden unforeseen crisis when a generation of over 120 million people turns 60?

Will there perhaps be no significant change realized?

Might this inevitable trend be a blessing in disguise that can be embraced and utilized in unexpected ways?

While it is difficult to definitively answer how China will cope with the inevitable ageing of its biggest generations, it is possible to predict how this situation will be handled based on what it the country is already doing, as well as its plans for the future. It is first necessary, however, to understand what an ageing population entails, as well as how this situation has evolved.

China’s Ageing Population

China today boasts enviable societal and economic statistics, having undergone a drastic demographic transition as well as vast economic reforms that have revolutionized the country in under 30 years. As a result of this and the one child policy, China’s population growth rate has stabilized from a staggering 2.5% in 1963 to an average yearly rate of roughly 0.52% per year since 2009. Likewise, China has experienced one of the most successful international cases of economic development, with its GDP per capita growing 240% since 2000 and drastic improvements seen in nearly all data figures related to human development. One of the direct effects of these changes is a decrease in mortality and an increase in life expectancy—from 72 years to 75 years since 2000.

While these statistics are undoubtedly positive in the present and provide China with such luxuries as an ample and youthful labor force, a looming societal crisis potentially rests on the horizon. Although the population growth rate has successfully stabilized, it has created an unbalanced and fragile age dispersion. In the years ahead, as China’s baby boomers reach retirement age, the country will transition from having a relatively youthful population, to a population with far fewer people in their productive prime.

This trend of ageing and scope of decline is best expressed in numbers. China today boasts an impressive five workers for every retiree. By 2040, this highly desirable ratio will have diminished to about 1.6 to 1. In addition, by roughly 2050, the median age in China will go from under 30 to around 46, making China one of the oldest societies in the world. At the same time, the number of Chinese people older than 65 is expected to rise from roughly 100 million in 2005 to more than 329 million in 2050—more than the combined populations of Germany, Japan, France, and Britain together.

The consequences of these projections for China’s finances are potentially harrowing. With more people soon exiting the workforce than entering it, the fiscal costs of having elderly people far surpass younger people in numbers will grow and likely eventually require the creation of a modern national pension system. An additional issue arising from China’s ageing population is the country’s hundreds of millions of ageing farmers and migrant laborers— a segmentation of people who have limited to no personal savings and only fundamental retirement coverage. Additionally, with agricultural and hard-labor careers quickly loosing favor with younger generations, these important sectors could suffer an immense blow in the future.

Steps Being Taken

Perhaps the most noticeable step already taken to address the inevitable trend of ageing is the gradual reversal of the one child policy— the family planning regulation introduced between 1978 and 1980. Originally intended to better monitor and stabilize the rapid rate of population growth, the one child policy began loosening its restrictions gradually throughout the 21st century, finally phasing out completely in 2015 as a preliminary part of the 13th five year plan. Today, it has been formally replaced by the two child policy, which is intended to reduce the pressure of the ageing population while increasing the labor supply and promoting balanced population development.

Although this physical repeal of the one child policy may help ease the population time-ticking bomb to some degree, the two child policy will most likely not be sufficient to cater to the lopsided population distribution. As such, the second major step already being enacted is a change of mindset regarding the perception of the older generation. With time, China has realized that coping with its ageing population while preserving economic growth is not something that can be adequately reversed at appropriate speed. Instead, it must be embraced. Hence, rather than disregard older generations as a burden to society, there has instead been an effort to shift societal attitude towards how to keep the colossal ageing population happy, healthy, active— and working.

China’s Future Plans

Recent years have seen an increase in public policy proposals and conferences addressing China’s ageing population. One such event, the 2016 “Shanghai Roundtable on Active Ageing”, outlined a unique plan of action to tackle the ageing issue— one that embraces the existing societal situation by engaging older workers in the workforce. By leveraging its ageing population and developing policies to keep the older generations active and needed members of society, China stands to maintain or otherwise transfer its existing powerful numbers into the future.

This course of action requires massive training programs and the creation of new learning opportunities to help incorporate older citizens back into the workforce. By designing an ecosystem that gives seniors a way to contribute back to society via services such as home cooking, history lessons, traditional crafts, or babysitting, it allows for the vital regaining of a sense of purpose. Thus, rather than being treated as dependent members of society that ‘fall burden’ on younger generations, China’s older generations instead become valuable, respected and important members of society that all younger generations can and should learn from. However, should China want to truly embark on this path, it will have to restructure and adjust many existing aspects of urban and rural society— be it by improving infrastructure to make it more accommodating to those with disabilities, to otherwise leading global healthy ageing campaigns.

Another proposed course of action has been to embrace the notion that the 60+ demographic in China will inevitably soon become the prime demographic and consumer group in China. This plan of action revolves around the idea that, by catering rather than disregarding older demographics’ needs in fields like healthcare, technology or retail, not only will this benefit the economy, but also the quality of life for the elderly.

Finally, regardless of if China follows through with proposals to embrace its ageing population rather than treat it as a problem, one immediate issue that must be addressed is the special needs of the 80+ demographic— the most rapidly growing segment of the population. As life expectancy increases, technology will become key to elder care-giving, especially considering China’s set goal of 90% of this demographic “ageing in place” at home. As such, China has to be very quick in establishing the social protection and welfare state which has already been in development for over 100 years in Europe. Furthermore, from telehealth and telemedicine, China will have to open its borders to the best of what is produced across the globe. Hence, free trade is essential as China confronts its ageing population.

Together, these several courses of action serve to both manage the ageing society as well as help reignite and modernize fading traditional values like the Confucian ideal of respect for the elderly.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the more China stares its daunting future straight in the face and takes action in advance, the more the situation can be transitioned from burdensome to a blessing. China’s numbers are currently a major asset in allowing it to rapidly enact widespread changes and massive reforms. Should China continue embracing these numbers, even as they grow older age-wise, it can continue sustaining its powerful economy, while at the same time promoting mutual respect and beneficial dependency among the varying generations.