China Fine-Dining Market:

Note from Myung Jee Jang, Mio Sato & Maya Cypris– In 2016, we received a year-long research grant to investigate where China’s fine-dining stands in the world market. While the topic may sound somewhat novel, we truly believe that this research has great value in divulging information about Chinese culture, perception of innovation, and global expansion plans. The following, though only part of our final report, highlights our research process and covers some of our many findings.

China has been living out a Cinderella story of sorts, with an ever-growing collection of rags to riches stories. With a new consumption culture in place and money to spend, many urban Chinese civilians have experienced notable improvement in their quality of life. While the country’s rapid success and development has yielded a plethora of high-scale amenities, goods, and service— including elaborate new shopping malls, spas, luxury hotels, theaters, international university programs etc…, one sector which has not evolved and matched Western standards as rapidly is that of fine-dining. Fine-dining is considered to be a luxury closely associated with wealth and fortune, and indeed the countries who are known to be leaders in the fine-dining sector are for the most part also economic world leaders. As good-quality food is considered a status symbol, a country that can afford to invest in developing this sector is likewise usually considered powerful and successful.

In the world of cuisine, the highest recognition a restaurant can receive is by consistently topping renowned world rankings such as the Michelin Guide, La Liste etc… However, despite China’s enormous population and millions of restaurants throughout the nation, only a meager few have been able to join this prestigious club of fine-dining superiority. Food supremacy is a form of creativity, and successful restaurants are often praised for being innovative, unique and inventive—all traits that China is tirelessly working to embody. With a five year plan oriented around innovation in place and an incline to be recognized as a global leader across all industries from higher education to hi-tech, it appears odd that the culinary industry has been seemingly left behind. The fact that the country’s huge restaurant industry is not a chart-topper by world standards when it has excelled and grown in so many other fields quite contradicts its current powerful global status— and perhaps indicates a greater underlying problem.

Chinese food culture is rooted in simple snacks and a wide range of specialties originating from different regions… In spite of the fact that it is a capital city, Beijing does not leave much room for chefs to improvise.”

– Hong Yip, Food Columnist

Defining Fine-Dining

The first explanation for the seeming lag might come down to semantics and perceptions. The grasp of fine-dining and what it constitutes differs from east to west, and can divulge telling tidbits regarding what each region sees as creative, exotic or valuable. In Western fine-dining establishments, there is often a course-menu provided, alongside a typically minimalistic aesthetic that caters to the “less-is-more” ideal. Portions of food are typically smaller than can be found at a more casual or family-style restaurant, and the notion of visually “plating” the food in an elegant manner can be considered just as important as the taste. The high emphasis placed on ‘culinary innovation’ in Western fine-dining means that food creation is grasped as an art form rather than just cooking. Indeed, the most admired and successful chefs have often been those who have found new ways to create, showcase and honor their edible medium. This “respect” for the food extends to the dining atmosphere as well, as Western fine-dining establishments usually have a formal atmosphere where proper etiquette and dress is expected of diners. In this sense, just as making the food is an art for the chefs, going to a high-end restaurant is an experience rather than just a dinner for the customers.

When defining the concept of fine-dining from a Chinese perspective, it is primarily interesting to note that the term ‘fine-dining’ cannot so much be translated into Chinese as it has no direct equivalent. Alternatively, the concept of different food experiences can be explained with phrases such as 高级餐饮 (gāojí cānyǐn- high level dining), 正式餐厅 (zhèngshì cānting- formal restaurants), and 正规餐饮 (zhèngguī cānyǐn- regular dining). This differentiation alone demonstrates a challenge when attempting to standardize the international fine-dining industry. In contrast to the simplistic aesthetics of décor and food in Western establishments of class and luxury, China’s culinary world demonstrates opposite taste. As is common in many Chinese restaurants, a Chinese fine-dining experience is synonymous with the word ‘abundance’. Ranging from an immense menu filled with ample food options of bold flavors, to more heavy-handed décor, China values lavishness and diversity. This abundance does not contradict high-quality and fresh food items, but rather emphasizes the importance of options and choice. This likely stems from China’s history, where only the wealthy could enjoy the diverse richness of cuisine. Furthermore, as opposed to Western fine-dining’s appreciation of innovation in cuisine, China still highly values its existing wide variety of traditional dishes that have been the same for hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

In regards to the dining experience itself, Chinese dining is typically a very communal affair as opposed to the individualist Western approach. Since everyone shares, dishes are packed with food and everyone can taste from everything that is ordered. When applying the concept of “fine-dining” to this eating culture, what is most prominently added on is high-quality service— the likes of which are found in Western fine-dining establishments. This attentive service is rather exclusive to China’s fine-dining culinary sector only, as the absence of tip-culture in China makes for waiters who typically have less incentive to fully exert themselves. Finally, unlike in Western fine-dining, though Chinese upper-end establishments also work hard to create a formal atmosphere by Chinese standards, there is a more lax approach in respect to creating a holistic luxury experience. Most Chinese restaurants of any scale don’t employ a dress code and allow customers to wear whatever they want.

In defining the variables and scope for our study, it was important to differentiate that many restaurants in China could be run by either Chinese or Western chefs who might have different culinary backgrounds, cultural inspirations and influences in their food creation. Therefore, our research specifically focused on fine-dining establishments that served Chinese food, while noting whether they catered to a local or international audience.

Culinary Ranking Systems

Another path with which to analyze the predicament of China’s fine-dining market is to explore the world of global restaurant rankings, and better grasp how objective they are, which ones are considered most reliable, what criteria they base their rankings on, and more. All rankings are to some degree personal opinion, and it is thus inevitable that regional prejudice or bias might skew the picture. If many of the leading rankings are European-based, for example, they could consistently favor European or Western-style restaurants rather than those in China that are more influenced by Chinese culture. It is also worth considering that some international rating systems, like Michelin, have only recently established offices in China, putting Chinese fine-dining out of the relevant radar for quite some time. Meanwhile, despite not making many world rankings, China has numerous ranking scales of its own which show a decidedly different picture.

Western Culinary Ranking Systems

The Michelin Guide

Perhaps the most internationally renowned of all global culinary rankings is the Michelin Guide, a French ranking system which has been dolling out coveted stars to a select few establishments since 1926. Originating from a tire manufacturing company’s guidebook for French motorists that included a restaurant review section, the column quickly began garnering attention and eventually evolved into a separate branch entirely. Today, undercover food critics are sent to unsuspecting fine-dining establishments worldwide where they can potentially score one, two or three stars. Each star is earned or lost from an additional visit to the establishment, during which another star will be added if the new experience surpasses the last. The inspected restaurants are generally those who have generated enough buzz in the culinary scene to attract Michelin attention. As such, this ranking system can potentially also award stars to less likely candidates, should the restaurant build a good enough name for itself. Such was the case when Michelin awarded Hong Kong restaurant “Tim Ho Wan, the Dim-Sum Specialists”, its first star in 2010, a feat dubbed “the world’s cheapest Michelin star restaurant”.

Stories like this prove that Michelin criteria does not exclusively consider price, although a hefty price tag is typically associated with a fine-dining experience. In fact, the only known Michelin Star criteria used to judge a restaurant are— quality of the products, mastery of flavor and cooking techniques, the “personality” of the Chef in his/her cuisine, value for money and consistency between visits. As these points are all rather open-ended and tend to put emphasis on quality rather than fancy embellishments, this leaves quite a lot of potential and leeway room to rate Chinese restaurants according to the local culinary values of the country. Indeed, as Michelin has only begun awarding stars to mainland Chinese restaurants since 2016, they have accordingly been adjusting their criteria to match Chinese fine-dining standards as much as possible.

The newly released 2017 Shanghai Michelin Guide is a historic first for mainland China, with 26 restaurants taking home stars. These restaurants range from housing Western chefs to Chinese chefs, with approximately half featuring Chinese food—our focus in the study. Parsing some reviews, these Chinese Michelin Restaurants were scored high because they “uniquely preserved the traditional flavors of Classic Chinese dishes” and “displayed exquisite oriental elegance in both design and plating”, among others. The addition of these 26 restaurants to the prestigious Michelin Stars list perhaps debunks the assumption that Western rankings routinely favor Western food and fine-dining style. It is worth noting, however, that when we began our research in early 2016, the only Michelin restaurants in China were in Hong Kong, so this new appreciation of Chinese fine-dining cuisine could be a result of China’s rising global status in the world. Still, there is a long way to go for mainland China’s top restaurants to be wholly renowned on a global scale. As expected, these Michelin restaurants are all in the top-tier Western-influenced city— Shanghai. Furthermore, they all seem to cater to a decidedly Western audience looking to try a high-quality and authentic Chinese dining experience. Hence, while it is true that the Michelin rating system can adjust to fit Chinese culinary ideals, there is also perhaps some mutual adjustment made by the Chinese dining establishments to appeal to the traditional Western fine-dining experience as well.

La Liste

A newcomer to the global ranking scene, the French La Liste was founded in 2015 and quickly rose to become highly acclaimed in the culinary world. Perhaps what makes La Liste so widely credited and reputable is that it designed in a way to make it as objective and all-encompassing as possible. La Liste compiles data using a processing algorithm which factors in 200 international dining guides, crowd-sourcing sites (such as Yelp and TripAdvisor), New York Times and Washington Post reviews. It also takes into consideration other rankings including Michelin, Zagat, the James Beard Award, and the OpenTable. As such, it introduces mathematical validity to the otherwise subjective topic at hand. What is further unique about La Liste is that it also provides a trustworthy index to appropriately weigh the ranking scores of each included guidebook and fine-dining list. This index is intended to solve problems such as lists favoring restaurants from their own countries, business connections, etc… La Liste’s intricate system ultimately ranks the world’s top 1000 restaurants and gives each a maximum score out of 100.

Taking into account La Liste’s wide parsing of data, it can perhaps be considered the most accurate source with which to observe how China’s Chinese restaurants rank on a global scale. However, as La Liste essentially does not define specific criteria associated with fine-dining, like Michelin does, but rather lumps public and professional opinion together, it is not necessarily the best indicator of fine-dining per-se, but rather of an overall inclusive dining experience.

On a country-wide level, China ranks in 4th place, housing 69 restaurants on La Liste. But despite the impressive country ranking, upon further inspection it becomes clear that China’s achievements fall short when compared to other countries, especially considering its size and number of restaurants throughout the country. Of the 69 restaurants from China on La Liste, the restaurant that makes the highest ranking is only in 42nd place. This ranking stands rather far from the countries in 1st (Japan), 2nd (France) and 3rd place (USA)— all leading economies whose top restaurants come in at 3rd, 4th and 2nd place on La Liste, respectively. This shows that while China may on a macro quantitative level have globally top-ranking restaurants, on a micro qualitative level China’s top ranking restaurants do not match other countries that are culinary leaders. Furthermore, of China’s 69 top restaurants, 22 are in Hong Kong and 4 are in Macao. As these regions are heavily western-influenced and not considered mainland China, it is safe to say that only 43 mainland restaurants in China made La Liste’s top 1000 ranking. Paired with the knowledge that China’s highest ranked restaurant is at the low spot of 42, and considering that China proportionally to other countries has far more restaurants and thus potential to place on La Liste— China indeed seems to be genuinely lagging on an objective global culinary scale.

Chinese Culinary Ranking Systems

Dàzhòng Diǎn Píng (大衆点評)

Compared to Western ranking systems, Chinese ranking systems are an entirely different ballgame. The most famous Chinese Culinary Ranking System is arguably Dianping (大衆点評). As it is an entirely Chinese platform, Dianping is little known outside of China, but is a giant in its domestic market with a 4 billion dollar valuation. Established in 2003, the mobile-internet company already has more than 600 million users— an unbelievable figure that essentially means half of the Chinese population uses this system to search for their favorite restaurants. As such, the service has had significant influence over the Chinese culinary market and has played a part in shaping Chinese people’s modern food culture and lifestyle.

As is common in many different Chinese market sectors, Dianping is not solely a one service product, but rather a whole platform. Like WeChat is to Whatsapp and Alibaba is to Ebay, Dianping covers far beyond restaurant rankings. The platform provides all kinds of lifestyle information, ranging from hotel info to various entertainment categories like KTV (Karaoke TV) bookings, salons, shopping, exercise and more. The restaurant section uses GPS to search for the nearest establishments, even allowing users to later pay for their meal through the popular Chinese online payment system- Alipay (支付宝). Moreover, customers who are referred to a restaurant through Dianping enjoy a significant discount, further incentivizing usage of the platform.

Dianping is a unique ranking system compared to the Western ones covered earlier in that it is a 100% public opinion ranking system- much like Trip Advisor. As opposed to Trip Advisor however, it is essentially the country’s primary and most trusted fine-dining ranking service. The Dianping ranking utilizes a 5-star system to judge its featured restaurants, with 5 stars representing the maximum 10 points attained in each of the three main criteria- taste, atmosphere and service. Unlike other standard rankings however, Dianping does not have a grand ranking of all the restaurants on its roster. Rather, each establishment is scored individually and independently of others. Still, since Dianping is designed for Chinese consumers and only features restaurants within China, the scores of these restaurants truly reflect the standard Chinese culinary preference.

As it caters to a Chinese audience, Dianping is decidedly dominated by rankings of Chinese establishments in China. Showing the vast diversity and richness of Chinese cuisine, numerous restaurant categories are arranged by themes such as region and province, offering sections featuring Jiangsu cuisine, Yunnan cuisine, Xinjiang cuisine, etc… Conversely, the number of foreign restaurants featured on the platform is extremely limited compared to Chinese cuisine. In fact, only 3 out of the 26 food categories are dedicated to foreign cookery— Korean, Japanese and general Western cuisine.

Meituan (美団)

Another famous Chinese ranking system is Meituan(美団). What makes Meituan special is its delivery service in addition to the Dianping-style rankings. The platform truly revolutionizes the general grasp of a dining experience, with food from thousands of restaurants, including fine-dining establishments, potentially delivered to people’s home within the hour. Furthermore, Meituan normally also offers a significant price discount with these deliveries—making fine-dining food potentially more affordable and accessible to all income groups. Hence, while the Chinese culinary world is sometimes critiqued for serving consistently traditional dishes without the culinary food innovation in the West, the Western culinary ranking system world can equally be criticized. As seen with Dianping and Meituan, Chinese ranking systems are far more innovative than those in the West which only provide concrete information about restaurants- without additional features that complement the dining experience. The wide scope of service and price discounts of these rankings make them immensely popular and successful, attracting almost the entire market share of restaurant connoisseurs in China. In this sense, fine-dining in China is less exclusive than in the West, with the utmost value placed on the taste rather than a select experience.

Lastly, what is perhaps most remarkable about these two big ranking systems is their recent merger into one joint venture company in 2015. Due to the intense competition in the Chinese culinary sector, Tencent’s Dianping and Alibaba’s Meituan settled the rivalry by merging together to make the biggest O2O company in Chinese history. The current monopoly of Dianping and Meituan means that these players and their rankings have a significant impact on Chinese food culture, far more than Western rankings like Michelin or La Liste have on their respective markets.

Restaurant Visit Case Studies

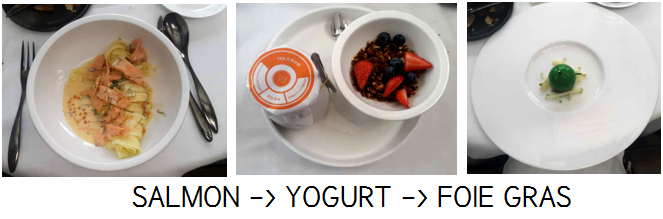

In the operational part of our research, we selected 3 top-ranking restaurants in Beijing to help enhance our understanding of fine-dining in China. In this public online version of our research paper, we have elected to withhold the names of the 3 establishments as we do not wish to openly critique any brand and instead prefer to focus on the culinary aspects at hand. As our study was limited to only Beijing, we did not have the opportunity to visit any of China’s newly minted Michelin restaurants or the top-ranking La Liste establishments in Shanghai or Hong Kong. Still, our selections have nonetheless all succeeded in earning raving reviews on online food rankings both internationally and locally.

‘Restaurant A’: Control Group, Western Food, Western Chef

As we had no access to internationally chart-topping establishments, we wanted to select a high-ranking Western restaurant to best represent the Western fine-dining market and values. Of the Western rankings we analyzed, ‘Restaurant A’ only placed on La Liste, coming in at almost 900th place out of 1000. Of the Chinese rankings we analyzed, the restaurant scored well, earning a score of 27/30 (translated to 5 stars) on Dianping.

At ‘Restaurant A’ we had the opportunity to interview the restaurant manager, Li, who told us about the restaurant’s history and target audience. Li expressed his vision, saying the restaurant serves “contemporary authentic European cuisine and is committed to providing the highest levels of hospitality for the guests, who are mostly Chinese”. The establishment compound— a historic renovated Temple tucked away in Beijing’s hutongs, has 600 years of history incorporated into the walls, including ancient halls of worship, factories constructed after the Communist takeover, and slogans left over from the Cultural Revolution. As is evidenced by these facts, ‘Restaurant A’ is a unique combination of East and West. It is on one hand an establishment owned by a Western chef that serves European food, while on the other hand it caters to a mostly Chinese audience and takes immense pride in preserving the authentic Chinese structure it is located in. This is perhaps a prime example of our earlier consideration, which assumed that the restaurants that score high in China are to some degree mutually catering to Eastern and Western ideals alike.

From our experience, eating at ‘Restaurant A’ was much like eating at a fancy restaurant in any other Western country— a likely reason why it has generally earned high reviews on Western rankings. The menu offered a small amount of select dishes and was arranged into courses, with every item explained and detailed by the server beforehand. The service was highly attentive and the food was presented in elegant small portions as is common in Western fine-dining.

Perhaps the two most prominent observations from our time in ‘Restaurant A’ that do not so much fit the typical Western ideals of fine-dining were related to dress-code and course order. As explained earlier, dress-codes are common in the West as they help create a formal atmosphere. However, as Chinese fine-dining ideals do not place emphasis on this, it seems clear that ‘Restaurant A”s lack of dress-code is to accommodate its many Chinese diners. Hence, people could be seen wearing anything from sweatpants to an elegant cocktail dress. Furthermore, Western fine-dining places great importance on the order of food, with certain dishes always preceding others and a clear distinction between appetizer, main course and dessert. At this establishment, while there was some ordering of courses, some of the dishes were served somewhat illogically to the Western palate— with a standard appetizer meal served after a dessert preceded by a main entree.

This is perhaps more in accordance with Chinese dining, in which there is no clear distinction between the labeling of courses. Evidently, despite our efforts to treat ‘Restaurant A’ as a control group, this was not entirely possible due to the mixed Western and Eastern nature of the restaurant. Still, it did provide us with valuable insight into Western fine-dining ideals which later served as a comparison point to the Chinese restaurants we visited.

‘Restaurant B’: Chinese Food, Chinese Chef

The first Chinese restaurant we visited is widely known for its Beijing specialty, Peking duck. While it has not ranked on any of the Western rankings we analyzed, it was named the 2014 Best Chinese cooking style restaurant in Beijing by The Beijinger as well as scoring a perfect grade on Dianping. In terms of meeting Chinese fine-dining standards, ‘Restaurant B’ was very much representative of the country’s culinary ideals. The menu was packed with food options, with the décor of the restaurant abundant and vibrantly colorful, and the service highly interactive— involving the classic demonstration of cutting the duck in front of the table. While there was no dress-code for diners, the waiters were all donned in a standard black uniform. Although ‘Restaurant B’ has not formally placed on many international scales, perhaps due to its very Chinese nature and interpretation of fine-dining, it has caught the attention of many individual Western food critics. These critics have all praised ‘Restaurant B’ for its exceptional food, atmosphere, and proud display of Chinese traditional cuisine. Many reviewers have noted that the restaurant stands out from other Chinese establishments for its innovative methods of cooking Peking duck. A CNN travel article states that “(‘Restaurant B’) does Peking duck for the 21st century” and that it is an “artistic conception of Chinese cuisine”. Observations such as these show that even though China highly values its native food customs and is perceived by some to be conservative in this field, its food culture has far from stalled. This realization is important because fine-dining is typically associated with culinary innovation, at least by Western standards.

‘Restaurant C’: Chinese Food, Chinese Chef

‘Restaurant C’, located near the city’s iconic Lama Temple, was an obvious choice for our study as it truly personifies a Chinese restaurant that caters to Western fine-dining ideals and hence tops many international as well as domestic rankings. The vegetarian restaurant is listed as Beijing’s #1 restaurant on Trip Advisor (out of 11,000) and is ranked 572nd on La Liste. On Dianping, ‘Restaurant C’ earns a high 27.6 points, translating to 5 stars. The target audience of ‘Restaurant C’ is geared very much towards Chinese diners, with both their website and the waiters communicating only in Chinese.

The first most prominent observation to an outsider upon arrival at ‘Restaurant C’ is the beautiful and delicate layout and atmosphere of the restaurant. Much like Western fine-dining establishments, ‘Restaurant C’’s design is clean, simplistic and modern— a vastly different style from the vibrant decorations common in most Chinese restaurants. Harp players were placed in the middle of the circular restaurant, playing live music amidst water mist that lightly sprayed from the ground. All together, these elements created a truly enchanting and mystical feeling that elevated the whole dining experience. The menu, like in ‘Restaurant A’, was arranged in set-course meals, with a price-range that required a pretty penny to enjoy. In terms of service, while there was clearly top-notch attentiveness to each diner’s every whim, there were also some fine-finishes that could be considered a bit unusual by Western standards. Waiters escorted the diners everywhere, be it from the entrance to the table, to even waiting outside the bathroom. While in China this may be intended to convey emperor-like treatment, to a Western diner such service can be grasped as a bit excessive and uncomfortable. Furthermore, while there were many small touches that added to the culinary affair like napkins placed on the lap, this kind of attention was not consistent throughout the meal— with utensils staying unchanged from appetizer to dessert, and crumbs gradually accumulating on the table throughout the courses. Finally, when a waiter observed our table struggling to split a meal, she intervened in an effort to assist but ended up dumping the food onto two separate plates, thereby accidentally ruining the entire plating and appearance of the dish. In contrast to the very elegant way in which every dish was presented and explained beforehand, this unceremonious subsequent treatment of the food seemed inconsistent with the earlier aesthetic standard.

Ultimately, ‘Restaurant C’ was an interesting case study to analyze because it is a Chinese fine-dining restaurant that has worked hard to effectively meet many of the standard Western fine-dining ideals defined earlier. This is likely why it is far more renowned on an international scale than other Chinese fine-dining establishments. However, while it is successful on numerous levels and gives diners proper value for their money, upon further observation some problems come to light that are indicative of ‘Restaurant C”s uncertainty about its true identity. As evidenced above, there are certain Western qualities that Restaurant C tried to imitate, but perhaps interpreted incorrectly or didn’t fully understand the purpose behind. This misconstrued grasp of Western fine-dining ideals often resulted in odd-experiences that showed the restaurant is unsure of where it stands between the Chinese and Western fine-dining world. This problem is a common one to many Chinese restaurants who wish to appeal to the West, and is likely a major reason why China’s fine-dining market has thus far seemingly lagged on a global scale.

Final Observations: Western vs. Chinese Fine-Dining

As we attempted to tackle our heavy research question, we came to realize that the answer is not as clear-cut as it sounds. The world of fine-dining is subjective and vast, with numerous different variables and exceptions making it challenging to conduct comparisons. As such, there are clearly many factors that could be playing a role in why China’s fine-dining market is missing from many global scales despite its huge potential. It is difficult to conduct any concise experiment or reach definitive conclusions as every scale has its own operating model, and each restaurant is rated differently on different scales, caters to different audiences, is run by different people, etc… Still, on a whole, it seems that the main recurring theme between Western and Chinese fine-dining ideals is the different elemental grasps to what makes a heightened dining experience pleasurable. The difference comes down to the Western “less is more” approach versus the Chinese “the more the better” attitude. Clearly, neither interpretation of fine-dining is better than the other, it is just indicative of the different values each culture has.

On the whole, from our research we’ve seen that the Chinese restaurants that adjust themselves to fit Western ideals typically tend to rank higher on international rankings. With that being said, one concrete observation we are able to draw is that this phenomenon is changing. Fast changes are happening in the culinary sector in accordance with China’s ongoing massive evolution and increased globalization. Meanwhile, the West in turn has been making changes of its own to accommodate the exciting and vast market of Chinese fine-dining. China’s restaurants are increasingly placing more emphasis on service, food-aesthetic and creativity, while Western rankings are relaxing their rating criteria to put more focus on taste rather than surface indicators like price, design or fancy gastronomical gimmicks. When we started our research a year ago, the scene was decidedly different, with very few Chinese restaurants topping any international rankings, especially those in mainland China. Now, China’s fine-dining world already has a number of impressive titles to its name ranging from Michelin restaurants, to higher rankings on La Liste, and growing praise from Western food critics. It seems there is more of an effort made on both sides to cater and appeal to the other audience across the sea. The results of this mutual respect and open-mindedness has already become evident over the course of our year-long study.

Conclusion

Ultimately, we believe that a big reason behind China’s seeming lag on a culinary global scale is that fine-dining rankings are in and of themselves a western-birthed concept. It is worth mentioning that the very original restaurant rankings were all Western in origin. Furthermore, almost all Western rankings preceded Chinese rankings, with China’s most famous Dianping ranking only being founded in 2003. This is also evidenced by the lack of a direct translation for the concept of ‘fine-dining’ in Chinese.

Looking to the future, China’s culinary future is indeed evolving, despite its high priority to preserve its traditional cuisines. It would be inaccurate to say that there is no innovation in Chinese cuisine, as innovation is essentially change, and change is definitely happening in China’s fine-dining sector. There is also definite innovation in the services and features provided on Chinese ranking systems, as discussed earlier. Though this innovation is perhaps not as clear-cut as Western ideals of innovative cuisine such as molecular gastronomy or food that is treated as sculptural art, Chinese cuisine is finding new ways to bring its classic dishes into the 21st century. Be it through new presentations of Peking duck, to enhancing the overall fine-dining atmosphere by incorporating certain foreign ideals, China is learning from the world and developing its fine-dining sector. These changes may not be as obvious as in other fields such as manufacturing and entrepreneurship, but there is clearly an effort being made by both the West and the East to meet in the middle regarding culinary ideas. As China continues down this path, the future undoubtedly holds a global rise in status and respect for the Chinese fine-dining world.

If you have any further questions about this study, please do not hesitate to contact us:

2 comments

I think all of the US fast China express types should be added in a column There are thousands. When the average family eats out they view that as fine dining. Its a matter of interpretation. In China towns in the US I have found many high quality food kitchens. I have not seen one that only puts those pitences on the plate and call that find dining. Not to be picky.

The 8 major cuisines are of different features. Learn more about them and pick your Chinese food: https://blog.lingobus.com/chinese-learning-resources/8-major-style-of-chinese-food