Digital Healthcare Patient Experience:

The Chinese healthcare system is facing huge challenges with, on one side, a greying population, multiplying chronic diseases and poor health literacy and, on the other side, too few qualified doctors working in overcrowded top tier hospitals, lower tier ones being deserted. Digital Healthcare solutions are today multiplying to address the very obvious needs for higher quality of care and the associated market was recently estimated to reach USD 110 million in 2020 by BCG.

In this first article, part of a series analysing the digitalisation of the Chinese healthcare system, I explore the patient experience and the way Chinese start-ups are disrupting it, building China’s next generation of healthcare.

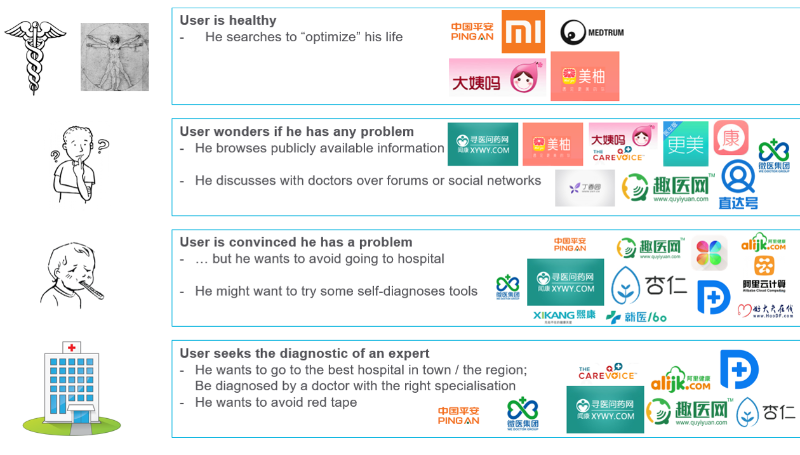

By default, the user is healthy. He can, however, still be interested in purchasing health-related products and services, ranging from pure wellness to soft healthcare. Most likely, those persons want to improve the way they live and believe in technology and the data it provides to do so. Wearables are answering this type of needs, such as Xiaomi’s Mi Band, tracking and monitoring key health parameters, easily understandable through the use of a specific app. It should be noted, however, that I have found only a few actors developing smart objects and associated data analytics/visualisation: is it because I have not searched long enough? Or is it because Chinese entrepreneurs are less likely to launch products targeting this segment? Two facts could support the last point: first, China has two distinctive innovation hubs for software (Beijing) and hardware (Shenzhen), making it complicated for talents of both disciplines to cooperate, which is needed to develop IoT solutions, and, second, Chinese innovation is known to mostly focus on business model innovation, rather than technological innovation. Interestingly, there are also actors targeting this segment without smart trackers but, instead, requiring users to input health parameters by themselves: that’s the business model of two menstruation-tracking apps that have respectively raised USD 30 and 15 million last year, Dayima and Meiyou (Meetyou). Their core business was to provide women with a reliable menstruation calendar, incrementally adding various other functions such as a social network or height, weight, sleep and mood tracking. Those smart objects and associated apps have also attracted the attention of insurance providers, such as PingAn, which now offer activity trackers with insurance packages for large companies, seeing in it a way to better quantify employees’ risks.

Next step is when the user starts to worry about specific symptoms he believes to have detected, and will therefore most probably start by searching their possible causes on the internet so as to determine how serious they can be. Many actors are positioning themselves on this segment, relying on different media: articles and blogs (TheCarevoice, Baidu’s Zhida, GengMei), forums (Dayima and Meiyou), databases of previous cases (Xingren Doctors’ Kanchufang), social networks of patients and, sometimes, doctors (Xywy, Quyiyuan, Dingxiangyuan), etc. I make the difference between this first step – at which there is still no direct patient-doctor contact – and the next one, in which the user starts to consider that the symptoms are serious enough to get in touch with an expert.

At first, he may not be willing to go to hospital for various reasons: he has little free time, hospitals are too crowded or he lives far from the closest trustworthy hospital or doctor. Several services address this specific need, such as online and mobile consultation, or instant messaging. Actors in this sector are very numerous, with names such as Haodaifu, Xywy, Quyiyuan, Chunyu Yisheng, Weiyi’s Guahao, Jiuyi 160, Baidu Doctor, Ali Health and Ping An’s Good Doctor. Some actors are also searching alternatives to online consultations with a doctor, which are difficult to scale up, by developing artificial intelligences capable of personalised diagnostic: Ali Health is claiming to develop such services, while IBM’s Watson is leading the way, though IBM is entering the market cautiously, only marketing Watson as an assistant for doctors.

Once the user is convinced he has something potentially serious, justifying a proper medical examination, he will consider going to hospital for consultation. He then has two main problems: first, he wants to avoid filling an endless number of documents and waiting for hours for the consultation and, second, he wants to be examined by a “good” doctor, i.e. with the right specialisation and able to diagnostic him in good conditions. Both problems are dealt with together by platforms with very similar business models but different geographical positions. Weiyi’s Guahao is the most important start-up in this field as it raised close to USD 900 million in 2015. Xywy, Baidu Doctors and Quyiyuan are also offering such services. At this stage and after, users are also anxious about their incoming experience and the quality of diagnostic they receive, and an increasing number of actors will try to fill this trust gap by providing information of all sorts on hospitals and their doctors: social networks (see above), reviews and feedbacks from patients (Weiyi’s Guahao, TheCarevoice,…), etc.

If doctors detect that something is wrong, he might want to hospitalize the patient for a day or two. I have surprisingly only identified one start-up operating at this stage, Xingshulin (Apricot Forest), who raised USD 14 million to equip doctors and hospitals with productivity tools, aiming indirectly at addressing the problems at this stage. Ali Cloud and Ali Health are also entering the market together, offering cloud computing-based solutions to optimize the ways hospitals are operating. Is it because operating directly with hospitals is much harder than with end-users? It might be because of a lack of standardization in hospitals IT systems.

After the diagnosis or after a certain time of hospitalization, the patient will be sent back home, with a more or less heavy treatment to follow. It can then be very challenging for him to abide by it, while his compliance is a key factor to the success of the treatment. One way to help him is to provide tracking solutions, such as smart objects or apps, as seen earlier. Even if Xiaomi does offer wearables able to track some health parameters, it does not specifically address such usages, requiring a data precision it is not ready to comply with. Vertical actors, however, have been entering this segment through specific diseases, such as the treatment of diabetes: Dnurse, Datangyi or Weitang. Forums, social networks and general articles can also be useful to improve the compliance through patients education (actors were listed above). In parallel, access to drugs is being increasingly facilitated by e-commerce actors partnering with major drug retailing companies: Shanghai Pharmaceuticals have recently signed a partnership with Jingdong, the main competitor of Alibaba’s Taobao, which itself has transferred its drug retail activity to Ali Health.

If the patient has any further problem, he will get to go back to hospital. In such a situation, it is then important that every stakeholder has access to data describing what happened to the patient in the past, either within the same hospital, in another one or at home. More than producing and storing patients’ data (here again something that wearables can do well), the challenge here is rather to standardize the way it is communicated between hospitals and doctors, so as to make it reliable. Ali Health is addressing the problem in partnership with Ali Cloud, thinking of storing those data in a cloud so that it can be accessible from anywhere by anyone with the right credentials. Haodaifu, a company that was founded in 2006 but raised USD 60 million in June 2015, seems to be willing to address the problem as well, trying to improve data sharing practices between hospitals, doctors and patients.

Digitalisation of healthcare is transforming every single step of the patient experience, from his general education on health matters to hospital operations. Start-ups are fully embracing this change by adopting data-centred business models, getting closer to customers than any other traditional company has been until now. So as to avoid disintermediation and remain relevant on the long term, traditional companies need to build their own digital access to customers, as the future of healthcare is going to be increasingly in the hands of those who have direct access to patients, capable of improving rapidly users experience and adapting to new changes.

Contact the author: