China Innovation:

Innovation is everywhere. It is behind every new idea, every solution to a problem, and any person who has dared to be different. But beyond the poetic nature of the term, innovation is also everywhere in the literal sense. The 21st century has seen the term surge in popularity, evolving into a buzzword that is heard daily in the worlds of business and economics. The direct implication of this overusage is the word’s eventual loss of meaning. When everything is innovation, then nothing is really innovation anymore.

Innovation is everywhere. It is behind every new idea, every solution to a problem, and any person who has dared to be different. But beyond the poetic nature of the term, innovation is also everywhere in the literal sense. The 21st century has seen the term surge in popularity, evolving into a buzzword that is heard daily in the worlds of business and economics. The direct implication of this overusage is the word’s eventual loss of meaning. When everything is innovation, then nothing is really innovation anymore.

China’s relationship with the word ‘innovation’ is an interesting one. Only three short decades ago, the country was struggling to make ends meet, with high poverty rates, a tormented national psyche, and widespread famine ravaging the country. But following the country’s massive reconstruction under Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms, China today is virtually unrecognizable from its 20th century past. A world leader in manufacturing and export trade, China has accomplished a remarkable transformation in a staggeringly short amount of time. Furthermore, beyond its arguably innovative macro transformation, China has also been gradually adjusting its growth model from industrial prowess to more sustainable value-creation in the form of entrepreneurship, private enterprises and consumption. It is clear that China has its eyes set on becoming the next great innovating nation. Indeed, when visiting businesses in successful SEZ’s like Shenzhen or urban metropolises like Shanghai, the term ‘innovation’ is thrown around almost synonymously with the word ‘China’. But as startups flourish and patent numbers grow, a great debate has been ignited amongst scholars. Is China really innovating, or is it just copying?

To answer this question, it is necessary to first define precisely what innovation is, as well as how it is measured. Only then is it possible to truly understand both sides of the debate and their respective arguments. With these facts and opinions acquired, the final section will ultimately evaluate whether the examples and claims presented rightly represent innovation or whether they are merely imitations of preexisting successful models.

What is innovation and how is it measured?

When trying to define innovation, it is important to distinguish between its quantitative and qualitative definitions. Generally speaking, innovation from a quantitative standpoint refers more to a macro level analysis in which entities such as firms or even a whole country can be evaluated based on measurable markers. Meanwhile, the qualitative definition of innovation is more ambiguous as it refers more to the micro level opinion of whether or not the product, concept, good, or service at hand is truly an innovation.

Operationalizing innovation is a complicated task as it essentially requires the quantification of the abstract idea of novelty. There are numerous different indicators that have traditionally been used to measure innovation. Generally, these indicators can be separated into two broad categories that include product & technology measures as well as financial & market measures. The product and technology category includes indicators that physically count the number of innovations and inventions produced by means of patents received, applied for, invention disclosures and contracts etc… Of these, by far the most standard indicator used to quantify innovation is the number of patents applied for and the number of patents received. Still, this indicator clearly has its faults as it does not account for the numerous other ingenuities that may have not undergone this formal bureaucratic process. In the financial and market indicator category, markers tend to measure aspects related more to the spending and resource allocation of the entity in question. This generally includes factors such as total R&D spending, number of employees in R&D, number of new markets entered, etc… Of these, R&D spending is generally considered to be the most accurate marker as this data represents the extent of investment spent on innovation and thus, to what degree investing in innovation is a priority.

While the aforementioned quantitative markers help paint a broad picture of an entity’s physical investment and application of innovation, these markers in and of themselves are not enough to properly assess whether an entity is actually innovating. Patents and R&D, as well as the other quantitative markers, could potentially also include goods or concepts that are heavily borrowed or inspired by others to the point that they are not truly innovative in their own right. Furthermore, while the number may be large, the quality of the patent or research work may not be up to par. Therefore, to truly account for the subjective value of innovation, and attain a better micro level assessment of the situation, the term ‘innovation’ must also be defined qualitatively.

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the term ‘innovation’ can be differentiated into 4 main types: product innovation, process innovation, marketing innovation and organizational innovation. Product innovation, the most widely recognized form of innovation, is defined most simply as “a new or significantly improved good or service that creates value or satisfies a need”. The other three types of innovation are quite straightforward in their names, referring to new or significant improvements in production & delivery, product design and packaging, and organizational methods respectively. ‘Innovation’ can furthermore be distinguished qualitatively as being either an ‘evolutionary’ or ‘revolutionary’ development, meaning an incremental new addition to an already existing concept, or otherwise an entirely new idea invented from scratch.

When used together, these quantitative and qualitative indicators combine to create both a micro and macro picture which can reveal an all-encompassing depiction of the Chinese innovation scene. These definitions and measurement tools will be applied for this purpose in the next sections, as arguments pro and against China’s innovation are presented.

Argument: China is NOT Innovating

It is impossible to deny that China has great motivation to increase innovation and entrepreneurial rates in the country. Indeed, China’s most recent Five-Year-Plan places unprecedented emphasis on developing these fields and encouraging their growth. However, those in the camp claiming that China is not innovating argue that China is largely a land of rule-bound rote learners—a place where R&D is diligently pursued but breakthroughs are rare. Hence, while the inspiration and incentive is there, the implementation and proper execution of creating true innovation is not. In other words, China may have the accomplished quantitative markers of innovation, but not the qualitative ones.

There are several main points often given to support this assertion. The first is that the common Chinese mentality is imbued in unity, saving face and obedience— traits which are contradictory to the development of innovation. Both China’s communist system and ancient culture have long stressed the importance of group unity. Rather than caring for their own interests and reputation first, there is more of a collectivist approach in which people are encouraged to think of the majority over the individual. This kind of ideology, while promoting harmony and common structure, strongly quells individual opinion and independence—both of which stand at the core of creative thinking. Furthermore, the stress placed on saving face means that people are wary of taking risks and standing out for fear of damaging their reputation. This too hampers the development of traits such as bravery and courageousness which are necessary for daring to think differently and try something new. Finally, as is valued in Confucianism, hierarchy and showing obedience to superiors is of high value in Chinese culture. While this philosophy often channels into positive qualities such as respect for elders, it also often exceeds into blind following of leadership- a factor which also stands in stark contrast to innovation. Thus, those who claim that China is not innovating argue that while quantitatively the government can try to mandate innovation through investment of national resources, R&D spending, and encouragement of patents, there are limits to what they can produce qualitatively that originate in deep-rooted Chinese culture and mentality.

The next main argument given to support these claims is that beyond the cultural limitations, there are fundamental structural problems within the government itself that further complicate the country’s motivation to produce innovation. Primarily, innovation in China is structured from the top-down, meaning that rather than come from entrepreneurs and enthusiastic idea-makers themselves, it is produced mechanically from the government down to its citizens. As such, many argue that even with all of the effort, China is likely to produce few world class authentic innovative companies. The strong role of the state and government in China means that much of the funding comes from the state, and the rewards are eventually meant to flow back to it. Thus, hierarchy and concealed control get in the way of anyone who aspires to be the next big successful entrepreneur of modern China. In addition, many also blame the government for the unprecedented scale of its failure to protect intellectual property rights. China is known to have a rampant copycat culture in which imitation is not only widespread, but is often even admired and respected. With heavy government surveillance and censorship, combined with lightly enforced IP protection laws, it seems a Chinese entrepreneur would have more difficulties to pursue a new idea and innovation than the average Western entrepreneur.

The final major point for this argument rests in the nature of Chinese innovation in its current form. A frequently employed strategy for developing innovation capacity has been through overseas partnerships and acquisition of innovation. Case studies such as Sany’s 2012 acquisition of Putzmeister, Germany’s leading cement pump maker, are prime examples in which a Chinese company could be considered innovative largely because of their newfound access to a past competitor’s technology. Furthermore, proponents of this argument state that Chinese companies must frequently resort to these foreign mergings because most Chinese start-ups are not founded by designers or artists, but rather by engineers who lack the creativity to think of new ideas or designs. Hence, it is argued that these type of employees struggle to step out of their disciplined and heavily structured comfort zone and resultantly will produce more superficial and mechanical inventions that have little imagination. Meanwhile, there are others who blame the Chinese education system, with its heavy stress on discipline and test scores, for subduing natural liberty of thought which is essential for innovation. This system has been criticized for placing too much focus on standardized success rather than encouraging individual performance based on each students’ own skill set and potential. This type of education extends to the home life as well, where many parents hope for their children to have prestigious careers as an employee in a steady workplace rather than doing something outlandish or entrepreneurial.

To summarize, the main gist of these arguments is that China’s current mentality, culture, political structure and priorities are not sufficient to support and create real innovation. Innovation entails coming up with diverse and challenging new ideas about how to do things differently, design things in a new way, or live in a different fashion, but the current Chinese system still rewards conformity. Proponents of this opinion often quote Chen Yun, one of the most influential leaders of the PRC during the 1980s, who famously said, “Innovation is fine – as long as it is like a bird in a cage. It has to be controlled”.

Innovation is fine – as long as it is like a bird in a cage. It has to be controlled”

Ultimately, these views clearly have great merit. But those who support the other side of the argument stress that these criticisms, while legitimate, don’t present the full story. These ideas will be explored more closely in the next section, alongside case studies of claimed Chinese innovations.

Argument: China IS Innovating

Going back to the qualitative definition of the 4 types of innovation. It seems the main dispute regarding China’s innovation scene is not so much in the process and organizational realm, but rather in the product innovation category. A country that over such a short span of time has managed to enact such an amazing turnaround from oppressed nation by foreign imperialism to becoming one of the financial world leaders, could not have done so without superb process and organizational innovation. The evidence is in the fact that no other country has managed to recover from such long-term trauma and evolve into the fastest growing economy so rapidly.

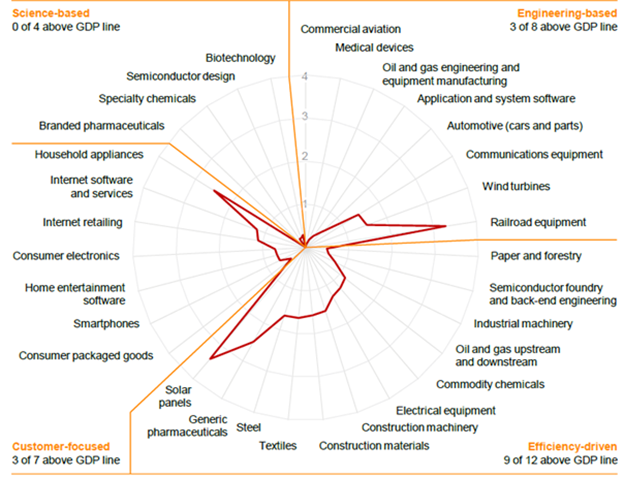

Further evidence which supports this claim is a recent study published by McKinsey. The research identifies four broad distinguishers among innovations ranging from science-based, engineering-based, efficiency-based, and customer-based innovation. Of these, the study found that China is remarkably successful in the efficiency-based innovation category, with 9 of the 12 main industries identified ranking above the GDP line. Furthermore, China also scored relatively well in customer-driven innovation, meaning that various markets such as internet retailing, smartphones, and consumer electronics have frequently been modified and changed to support new evolving consumer needs. The two categories in which China was weaker, science and engineering-based innovation, were again both fields relating to product innovation.

The revenue of Chinese industries in relation to their expected share of global sales, based on China’s share of global GDP. Credit: McKinsey & Company

Regarding this aspect of product innovation, supporters of the argument that China is innovating can first present the hard data of China’s performance with regards to the quantitative markers identified above. In the period following Deng Xiaoping’s opening up policy in 1978, many aspects of the Chinese legal system were reformed, introducing new laws such as the 1984 Patent Law which was intended to protect IP. Since its promulgation, China experienced a sharp patenting surge in 1999, in part reflecting the implementation of several key patent law changes in anticipation of China’s accession to the TRIPS (Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) of the WTO (World Trade Organization). Indeed, since then China has been granting an increasingly greater number of patents with every passing year, with over 208,000 invention patents granted in 2013. In terms of patent applications, 2014 saw China rank top in the world in invention patent filings for the fourth consecutive year, with some 928,000 applications for invention patents filed with the State Intellectual Property Office (SIPO)—an increase of 12.5 from the previous year.

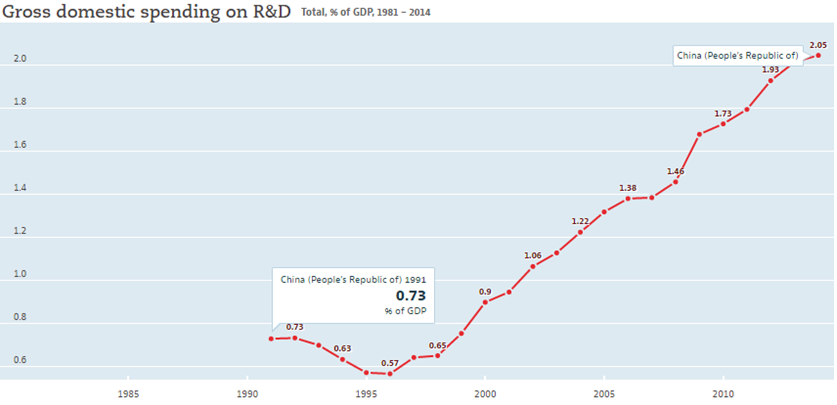

A similar trend can be observed when assessing China’s gross domestic R&D spending data. As documented by the OECD, starting from 1991 when the data began being collected, China’s R&D spending has risen steadily from 0.57 percent of GDP in 1995 to over 2.05% of the country’s GDP in 2015. This marks the first time China has spent more on R&D than the EU. While these markers may arguably not prove quality innovation in the micro sense, they still represent a drastic change in priority of Chinese resource allocation and areas of investment.

Beyond the arguments expressed above, perhaps the most full-proof evidence presented by proponents of ‘China as an innovator’ is case studies of successful Chinese business models. Namely, analyzing the stories of international giants such as WeChat, Xiaomi, and Alibaba help show that China is not just a process innovator, but also a product one.

Primarily, WeChat upon initial observation can be called a blatant copy of WhatsApp. But upon closer inspection, the application exceeds far beyond a basic messenger platform. WeChat has introduced an all-encompassing platform designed to allow users to better manage virtually all aspects of their daily life ranging from payment methods, transportation services, reservation features, digital healthcare, news distribution, social media and more. In fact, the platform has been so revolutionary that Facebook has recently announced a new set of soon-to-be-introduced features which all draw heavily from concepts invented by WeChat. The assortment of e-commerce features to soon be rolled out on the social network include allowing users to buy goods directly within the social network’s app, friend-to-friend money transfers, and ticket buying among others—all features that currently exist on WeChat.

A further case study is Xiaomi, a company which ironically is frequently cited as an example of China’s copycat culture. Xiaomi has often been criticized for producing near replicas of Apple products and advertisements, right down to taglines. While the CEO of Xiaomi, Lei Jun, does not deny this, he insists that these imitations are mere surface level copies of an already proven successful design and style. In an interview from Wired Magazine entitled ‘It’s Time to Copy China’, Lei Jun stresses that Xiaomi’s true success rests not in its appearance and slogans, but rather in its innovative business model. Xiaomi, unlike Apple, is not just a smartphone business, but rather a new kind of e-commerce internet-enabled ecosystem that goes far beyond smartphones, tablets, TVs and routers. Indeed, the company’s associated products include everything from games, to power banks, to IoT wearables, to air and water purifiers. Priced by its investors at $45 billion, the company briefly boasted the title of the world’s most valuable tech startup. Xiaomi also has a clear vision for the future of the company, one revolving around a key hot topic in the innovation world—Internet of Things (IoT). Lei Jun states in the article that “wearables, watches, scales and home appliances will be connected, and your Xiaomi smartphone will be the connector”.

Wearables, watches, scales and home appliances will be connected, and your Xiaomi smartphone will be the connector”

Finally, Alibaba is perhaps the most internationally recognized Chinese company in the world. However, while most associate it as an e-commerce and finance platform, the company too has been making strides in numerous other fields. Alibaba recently announced its Planet Streaming Service, a platform that is projected to change the global music streaming game and outplay the five big streaming company competitors- Spotify, Apple Music, Pandora, YouTube and Tidal. In addition to streaming video and music, the Planet platform is designed to enable artists to sell merchandise, stream live concerts, connect directly with other artists and fans, help merchants seek out celebrity endorsements, assist producers in selling beats to musicians, and more. The platform is further revolutionary in that it is open to all players of the music industry from music lovers, singers, composers, producers and merchants, allowing them to seek out relevant business opportunities. Supporters of ‘China is an innovating country’ argue that Alibaba, like WeChat and Xiaomi, is not just a product, but an all-encompassing platform, a multi-functional community, and an innovative business model.

In response to those who argue that China is a land of “rule-bound learners” that produces only “second-generation” or “evolutionary” innovation, supporters claim that a country that produces companies such as those mentioned above is clearly a “revolutionary innovator” in the purest sense. These companies all specialize in a wide range of industries and rework numerous aspects of daily life in a new way. This in and of itself, supporters argue, is a prime example of innovation. As a sidenote, it is important to mention that besides these big-name firms, startups and startup incubators are a whole other ballgame exploding in the Chinese market. Inspired by successful entrepreneurial capitals such as the Silicon Valley, startup hubs and entrepreneurial centers have seemingly emerged and multiplied overnight in all of China’s first-tier cities. Today, Chinese startups branch far and wide, and cover fields such as e-commerce, green-tech, IoT and more.

Conclusion

Where do these arguments leave us? To sum up, China is truly becoming an innovator on the macro level with increased investment in R&D and a steadily growing number of patents each year. Furthermore, China has accomplished an astonishingly fast evolution to become a global economic superpower, a feat which classifies under process and organizational innovation on a national scale. Regarding product innovation, it is also important to not neglect China’s impressive history of innovation and ingenuity that includes the Four Great Inventions that changed the world– papermaking, the compass, gunpowder and printing. In the more disputed contexts of micro-level innovation, it is fair to argue that China is still underdeveloped in terms of having a steady foundation for a prolific innovation scene. But despite the current cultural and structural barriers, it is clear that China is motivated to shift its prowess to the innovation realm and is trying to change and adapt to the times. And finally, while not all of China’s claimed innovations are necessarily 100% new, it is perhaps time to “innovate” our grasp of innovation. To quote the beginning of this essay, innovation is everywhere. It can be a process, a sweeping change, or a new advancement to an existing idea. Ultimately, from looking at the many case studies of successful Chinese companies that have developed entire platforms and communities for what was once a single product, to observing China’s miraculous 30 year evolution, it is clear that from an individual to a national level— China is truly innovating.