China Economic Growth Model:

“When the wind of change blows, some build walls while others build windmills.”

This classic proverb perhaps best encapsulates China and its evolving philosophy towards dealing with changing times. China of the late imperial era was a classic “wall-builder”, characterized by stubborn nationalistic pride and an oblivious sense of superiority that inevitably brought upon the Opium Wars and a century of humiliation. But ever a nation of the resilient of spirit, China’s traumatic era birthed a new understanding and stark 180 degree change in attitude that taught it to “build windmills” rather than resist the natural flow of times. Indeed, since the enactment of the Opening-Up Policy in 1978, China has consistently adapted and embraced the changing global patterns to great effect, often even revolutionizing and dictating the trends of the future. It is therefore no surprise that Li Keqiang, China’s State Council Premier, chose to quote this proverb to describe the future of China’s economy in his speech at the 2015 World Economic Forum.

Perhaps most significantly, this new ideology can be observed in China’s ever-evolving economic growth model. Under Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms, China embarked on a mission to modernize the country and transition towards a predominately export-led growth model. With an ample and industrious labor force, relatively low wages and productive investments, China had a strong preexisting foundation that it was able to utilize and channel into mass-manufacturing and export-trade. This new direction, paired with a distancing from the previous planned economy model, allowed China to attain double-digit growth rates in a remarkably short amount of time. However, as of late, the ambitious growth model has proven to be difficult to sustain, and GDP growth rate has begun to stifle and slow. Resultantly, China has gradually started turning its attention to new models of economic growth oriented around surprising directions– consumption and innovation. The following sections will introduce these transitions in more depth and explore China’s growth model evolution past, present and future.

From Planned to Mixed Economy

The first most identifiable turning point in the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) economic growth model is the transition from a planned economy, enforced under Mao’s Communist regime, to a mixed economy system. The Communist Party of China’s (CPC) planned economy placed all economic decisions ranging from the agricultural sector to the enterprise sector under the control of a central planning authority. It was enacted in order to improve and better regulate the severely underdeveloped national economy inherited from the Guomindang’s Republic of China (ROC) era. But rather than lead to economic growth, the implications of this all-encompassing power in one place were numerous and only further stagnated China’s economy. Perhaps most significantly, the planning committee members lacked crucial practical experience in fields such as agriculture and state-owned enterprises (SOE) which they were making decisions for. As such, they were inept to handle their important responsibilities that included determining the various sectors’ economic output, production goals, prices, and resource allocation. Furthermore, being detached from the relevant playing fields, the central planning authority frequently determined production quotas for farmers and SOE managers that were overly-ambitious and realistically unattainable, causing a severe lag between theoretical output and actual production. With Deng Xiaoping’s ascension to power in 1978, numerous reforms were implemented that were intended to correct these serious errors made under the planned economy system. The reforms marked a clear transition towards a mixed economy as China’s new economic growth model.

Incorporating elements of both a planned and market economy system, Deng’s dubbed “socialist market economy” introduced a two-tier system which gradually allowed enterprises to sell any production above the quota determined by the central planning authority. It furthermore enabled state-owned industries to sell their commodities at both plan and market price, thereby opening the market to forces of supply and demand rather than solely relying on predetermined conditions. Having more control over these essential economic decisions allowed SOE managers to make more educated choices for their sectors. This further served to increase their work incentive as they could more directly reap the fruits of their labor without having to constantly appease and surrender all their output to a higher authority. Deng’s reforms were revolutionary in that they not only developed the PRC’s economy internally, but also put unprecedented attention on the external strengthening of China’s economy to gain a firm global footing. As part of the opening-up policy, China was opened to foreign investment for the first time since the Guomindang era, allowing an influx of foreign capital into China. A series of special economic zones (SEZ) were additionally created, intended to ease the bureaucratic burden for foreign investors and domestic firms hoping to do business in the area. These regions became engines of growth for the national economy. Later economic reforms put more emphasis on expanding the private enterprise sector as an increasingly important component of GDP growth and the socialist market economy. While these drastic changes were enacted in order to propel China on the road to modernization, the mixed economy model on its own was not enough to sustain long-term advancement. Thus, the following decades began to see a shift towards new means of economic growth.

Shift to Export-Led & Investment Driven Growth Model

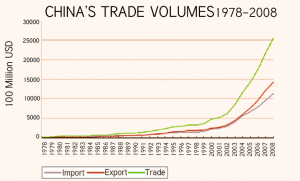

Much of China’s remarkable growth between 1978 and 2000 can be attributed to the economic reforms. But China’s even faster exponential growth experienced in the early 21st century has been mainly driven by exports. According to Prof. Yang Yao of the China Center for Economic Research (CCER), “China’s export-led growth is rooted in China’s double-transition of structural change and demographic transition”. On the structural level, Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms successfully improved the sectors of heavy industry, manufacturing, and infrastructure- a feat that Mao desperately tried but failed to accomplish during the Great Leap Forward. This rapid shift from a non-industrial to industrial society further induced a demographic transition during which the country transitioned from having a high fertility and mortality rate to a low one. Stemming from this double-transition foundation, China’s export-led growth model was onset by its admittance to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. As a WTO member, China was able to fully integrate into the world market and utilize its competitive advantage of an abundant and cheap labor force. Manufacturing and exporting produced goods were quickly found to be the country’s strong suits, and the iconic words “Made in China” were soon stamped on products worldwide.

As with most rapid wide-scale changes, China quickly experienced the inevitable side-effects of structural and stability problems that arose from the hurried transition to a new normal. Despite the county’s overall growth in GDP, household income rate did not increase nearly as fast, resulting in a severe lag in China’s consumption as opposed to governmental spending, investment and net exports. This heavy reliance on export-trade meant that China’s new growth model was very sensitive to the global economy and its demand for Chinese goods. Hence, when the 2008 global financial crisis hit, it resulted in a massive blow for China’s export-led economy. In its wake the recession left an unmaintainable economy that was primarily driven by excessive credit and investment. This hefty burden reportedly caused China’s debt to explode from $7 trillion in 2007 to a staggering $28 trillion by mid-2014. With prospects for growth under the existing model weakening, China began in recent years the process of reorienting its economy away from export and investment-driven growth towards a more consumption-driven model. This new direction has further involved a shift of focus towards a previously unencouraged realm—entrepreneurship.

Looking to the Future: Emphasis on Consumption, Entrepreneurship & Innovation

Having gleaned lessons from past mistakes, the CPC has over time adopted a more reserved approach regarding how to go about China’s future economic growth. With his inauguration to presidency in 2013, Xi Jinping called forth a new normal of gradualism as an overlying reform strategy. Rather than rely on a growth model that is fueled by investment and hampered by unsustainable debt, China’s new economic goals aim to achieve slower but more sustainable growth. This slowdown of GDP growth is already noticeable, as the growth rate has dipped below 7% since roughly last year, and is projected to be in the 6.5% range for some years to come. China has thus far enabled this transition by shifting focus towards encouraging growth in the service sector, consumer spending and private entrepreneurship.

Rearranging China’s GDP expenditure distribution has been an ambitious task to tackle as it has necessitated instigating a new national mentality. To truly reboot the economy as intended, consumer culture has needed to override saving culture. Under the mass-manufacture and export model, China’s massive underpaid labor force adopted a savings-mentality that greatly hindered consumption growth. Accounting for 50% of GDP in 2013, China’s gross savings rate were among the highest in the world. In an attempt to reverse this trend of unutilized savings, investments have been increasingly directed away from infrastructure projects towards improving civilians’ quality of life in an effort to encourage their spending. By investing more in health, technology and educational services, higher paying service sector jobs have been created that replace low-wage factory positions. As a result, household incomes have gradually been able to grow, thereby increasing consumer purchasing power and stimulating greater domestic demand. Allowing personal capital to grow and helping private sectors flourish has yielded a new workforce in China that is far more incentivized, productive and innovative than before. These elements are key to China’s future economic growth, as entrepreneurship and innovation have increasingly been recognized to be an integral element of modern economic advancement.

China has been a world leader in innovation and ingenuity for quite an extensive portion of its vast 5000 years history. Ranging from being one of the first civilizations to have a coherent script, to being the origin country of the Four Great Inventions– papermaking, the compass, gunpowder and printing, China has frequently been several steps ahead of the world in terms of creativity and originality. However, the 20th century marked a drastic turning point in China’s world supremacy, a time in which numerous traumatic events stifled independent thought and in its absence created a mentality of conformity and degenerative obedience. Thus, the past several years have seen greater focus placed on re-encouraging creativity and original thought. This new direction is evidenced in China’s most recent Five-Year-Plan, which places unprecedented emphasis on increasing innovation in the country. Inspired by successful entrepreneurial capitals such as the Silicon Valley, startup hubs and entrepreneurial centers have seemingly emerged and multiplied overnight. Today, Chinese startups branch far and wide, and cover fields such as e-commerce, green-tech, IoT and more. Results of this new direction are already evident, with success stories like Alibaba and WeChat shining as an example for big-dreaming Chinese entrepreneurs.

As can be seen, China has clearly begun making strides towards not only being the manufacturer of the world, but also the innovation hub of the world. Looking to the future, it seems that this new economic growth model is China’s new key strategy towards embracing the winds of change, and with it building windmills.

Read this article in Chinese here.

1 comment

Great page! Really enjoyed reading 🙂